A Better Funding Model for Affordable Housing

Why do we need affordable housing?

Everyone in Portland agrees: rent is too expensive. Apartments at reasonable prices are snatched up quickly, with crowds of people viewing them. Finding an affordable place to live is often a matter of connections, finding roommates, or sheer luck. The unlucky cannot find a home they can afford and end up leaving Portland or becoming homeless. These are the telltale signs of a housing shortage. Portland needs more housing, and more affordable housing, yesterday.

Portland has tried many policies to address the shortage. One important, recent step was ReCode, where the City Council unanimously adjusted zoning to allow more housing citywide. Early signs point to a success: some projects have been proposed that would not have been legal pre-ReCode. While the Urbanist Coalition of Portland’s recommendations for ReCode would have gone further in simplifying zoning and legalizing housing, we think ReCode’s passage was an important first step toward addressing the root causes of our housing shortage.

Unfortunately, there is another policy in Portland that is exacerbating the housing shortage. Originally designed to help housing affordability, this policy is called Inclusionary Zoning (IZ) and it is unintentionally contributing to rising home prices in Portland. Let's understand how Portland's IZ policy operates, why it falls short of achieving its goal of creating more affordable housing, and how a more successful policy might be implemented in Portland to achieve that same goal.

What is “Inclusionary Zoning” (IZ)?

Inclusionary Zoning is a confusingly-named policy that is neither zoning nor, we’d argue, inclusionary. The precise requirements are found in section 17.2.3, titled “Ensuring workforce housing”, of Portland’s Land Use Code. The section applies to “site plan applications that create ten or more new dwelling units for rent or for sale through new construction, substantial alteration of existing structures, adaptive reuse or conversion of a nonresidential use to residential use, or any combination,” mandates “at least 25% of the units in the project shall meet the definition of workforce housing unit for sale or for rent as defined in Article 3,” and offers “as an alternative to providing workforce housing units, projects may pay a fee-in-lieu of some or all of the units. In-lieu fees shall be paid into the Housing Trust Fund.” The fee for 2025 is $182,830 per unit.

In the simplest terms, Portland's IZ policy tells anyone who wants to build 10 or more homes that 25% of those housing units must qualify as workforce housing. Alternatively, they may pay $182,830 per unit into the Jill Duson Housing Trust Fund.

What is workforce housing? Here we enter a rabbithole of nested legal definitions. The definitions of workforce housing units require a rent or purchase price “affordable to a household earning 80% or less than of AMI.” “Affordable housing” is defined as housing with expenses (rent/mortgage, utilities, insurance, property taxes) that “do not exceed 30% of a household’s income.” AMI stands for the Area Median Income for the Portland metro area, calculated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). So, for projects with at least 10 units, 25% of units must have expenses capped at 30% of 80% of the Area Median Income for Portland.

This is a complex policy—try explaining “25% capped at 30% of 80% of AMI” while canvassing and watch the eyes glaze over. However, IZ was expanded to its current levels via referendum in 2020. This is a clear signal that Portland voters care about housing affordability and want policies that address this need. But, five years later, we have not addressed the shortage of affordable housing that continues to affect Portland. Under the current IZ policy, $0 has been deposited into the housing trust fund, and only one project, with 12 workforce housing units, has been built without additional public subsidy. Housing affordability and access, in some form, has been a City Council goal every year since 2020. We need to be willing to adjust policy when it isn’t working to achieve our goals.

Where IZ falls short

The goal of the Inclusionary Zoning policy is clear—growth should include affordable housing—and we agree with that goal. However, there are a few issues with Portland’s IZ ordinance as a policy solution. At its core, Inclusionary Zoning puts the entire responsibility for housing affordability in the hands of private developers building new multifamily housing. These new multifamily buildings must cover the cost and administration of affordable housing programs through higher rents and prices for multifamily homes.

Under IZ, affordable units remain privately owned and have a limited affordability term of just 30 years before all affordability requirements are dropped. Inclusionary Zoning began in the 1970s when America unwound its investment in public housing. It represents the privatization of a public social good. IZ keeps government spending low by pushing costs onto those who live in multifamily housing, and only those who live in multifamily housing.

The requirement affects only a narrow slice of all development that happens in Portland—housing projects of 10 or more units. Smaller projects or commercial development do not contribute anything toward affordable housing creation. This is especially problematic because multifamily housing is naturally more affordable than spread out development, thanks to shared land costs and infrastructure (streets, utilities, walls). Multifamily housing supports public transportation and walkable neighborhood businesses. Inclusionary Zoning specifically adds cost to the type of development we want to encourage.

Too-high Inclusionary Zoning costs prevent housing from being built, worsening our housing shortage. This is because projects complying with IZ are dependent on the revenue from market-rate homes to make up for the restricted prices of the designated affordable units. If the market-rate revenues are not high enough to cover the cost, potential homes in Portland go unbuilt, as homebuilders will instead build in adjacent towns and cities. This dynamic further cements Portland as an exclusionary, expensive place to live, as new housing can only be created when market-rate rents or home prices are high enough to also pay for the subsidized IZ units.

We aren’t getting much affordable housing from IZ, either. In the five years since Portland raised our Inclusionary Zoning fee, zero housing projects have contributed to the housing trust fund, and only one (Winchester Woods) provided any IZ units—just 12 units over five years. Projects have either provided affordable housing using other subsidized money (Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), MaineHousing dollars), are too small to require any contribution, or were approved under the prior, lower fee. Affordable housing built with LIHTC or MaineHousing dollars is great, but these funding sources are finite – necessitating their use in multifamily projects subject to IZ doesn’t create more affordable housing, it simply moves those affordable units around.

A successful IZ policy would create a new funding stream for affordable housing creation, either via direct developer creation or fee-in-lieu contributions to the affordable housing fund, both subsidized by market-rate profits. Our IZ policy has achieved nearly the opposite: developers are forced to rely on outside affordable housing subsidy money in order to create more than 10 units of market-rate multifamily housing. Projects subject to IZ have become competing consumers of affordable housing money in Maine, rather than new sources.

Analysis from the Urbanist Coalition of Portland found that our IZ requirement is higher than 90% of other localities that have adopted an IZ policy. People will debate whether our policy is at the point of having an exclusionary effect. However, this misses the fact that there is no single “point” beyond which our policy becomes exclusionary—rather, it is a blurry continuum with severe consequences for affordability if we make the wrong choice. We think it is best to sidestep this dynamic altogether, and instead adopt a policy that aligns the incentives between growth and affordability, without the possibility of these negative consequences.

A broader funding model

How new property tax revenue can fund affordable housing

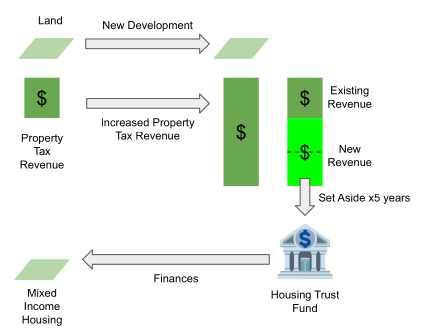

We propose a different funding model for affordable housing. We suggest capturing the increased property value of all development—new housing, commercial properties, major renovations—and allocating half of the added property tax revenue over five years to the housing trust fund for affordable housing creation. Think of this like a citywide Tax Increment Financing (TIF) district. More development directly results in more affordable housing dollars. And because we are capturing property value instead of assessing a fee, the disincentives against building housing are eliminated.

The approach naturally scales our investment in affordable housing with the amount of development in Portland. This ensures the city is contributing a sustainable amount while still capturing value from new development activity. If it is true that our current Inclusionary Zoning policy discourages the building of new homes, this change will add value to the tax roll, slow property tax increases and capture some of that value for affordable housing. If Inclusionary Zoning is not preventing development, and no more houses are built, then this change will not result in much new spending.

Consider the impact of different developments on the housing trust fund under this model, compared to current IZ policy. Imagine four example projects:

a 21-unit downtown apartment building

an 8-unit development off-peninsula consisting of 4 duplexes,

a new commercial building, and

a single-family home teardown and rebuild.

Under our current IZ funding model, only Project 1, the downtown apartment building, results in any contribution to affordable housing. However, our proposal would capture the increased value of each of these developments, giving us a broader and more equitable base of support for affordable housing.

In fact, our preliminary analysis shows that our value-capture approach, if it had been in place over the past 5 years, would have contributed more to the housing trust fund than current policy. The housing trust fund averaged $522,000 annually in housing fee-in-lieu contributions since 2020, all approved under our old IZ policy. We estimate that after five years, when the captured value is fully phased-in, the value-capture approach would add over $3 million annually to the housing trust fund. This is without accounting for the additional housing creation that likely would have occurred without the Inclusionary Zoning disincentive, further increasing the housing trust fund contributions.

We think this value-capture approach provides clear benefits over existing policy. Directing affordable housing dollars to the housing trust fund ensures our social housing initiative will have the resources to succeed, regardless of the approach the task force chooses. We believe affordable housing using city money should be permanently affordable, and ideally give the city an ownership stake that can be leveraged for future financing. These permanent affordability terms, and long-term ownership stake, cannot be guaranteed under IZ.

Capturing all development for affordable housing contributions ensures all growth helps meet our affordability goals. Shifting away from the construction-fee model removes the disincentive against the types of housing we sorely need. In this way, we align the incentives of developers and affordable housing advocates—more development means more affordable housing dollars.

Legal strengths

Portland could implement our funding model today without any need for enabling legislation from the state. It is administratively simple, and only requires a bit of math on top of existing tax assessments. Legally, this policy is not structured as a TIF but a level of commitment to the affordable housing fund based on new construction. The housing fund already exists and is already being used. Many municipalities use their budget to encourage housing affordability. Portland has the capacity to easily implement this policy.

The solid legal footing is not a mere curiosity. Recent Supreme Court cases, such as the unanimous Sheetz v. County of El Dorado, decided last year, suggest that the Court is interested in determining if impact fees, such as our Inclusionary Zoning fee, are unconstitutional “takings” in violation of the Fifth Amendment. There is particular uncertainty around Inclusionary Zoning impact fees, as impact fees require an “essential nexus” and “rough proportionality” that Inclusionary Zoning fees, by virtue of charging new housing to pay for new housing, may lack.

In contrast, our proposal does not use impact fees, but instead rests on the City’s unquestioned taxing and spending authority. Regardless of your views of this Supreme Court’s jurisprudence, we think it is best to ground our policies on a legal basis that minimizes Portland’s chances of an expensive lawsuit.

Encouraging Mixed Income Communities

One goal of Inclusionary Zoning is income mixing. Mixed-income communities promote social mobility, equity, and inclusiveness. But Inclusionary Zoning is not the only, or best, way to create these communities. In the past five years, the State of Maine created multiple statewide density bonuses for affordable housing, most notably in the statewide housing law LD2003.The Urbanist Coalition encouraged Portland to go above and beyond the minimum requirements of LD2003 and apply the affordable housing density bonus to all residential land on Portland’s mainland. This bonus has already led to the approval of a project with 156 new homes, 78 of which are workforce units. Affordable housing bonuses work to encourage more housing and mixed income housing.

We can also directly invest housing trust fund money in mixed income projects. These projects make housing fund dollars go further, with market rate units cross-subsidizing affordable units. This is one possible approach to Social Housing, and our value-capture model creates a new funding stream. Getting the most out of our housing dollars while building mixed-income communities is both realistic for Portland and would truly move the needle on housing affordability and equity.

When something doesn’t work, we should fix it

Five years after the pandemic housing price run-up, Portland’s affordability problem has not been cured. It is critical, as Maine’s primary city, that we are able to welcome residents of all income levels. The alternative is pricing out our neighbors and dealing with the symptoms of housing scarcity—homelessness, overcrowding, precarity. Portland voted for Inclusionary Zoning to express our desire for more affordable housing. We have seen this policy not have its intended impact, but this does not mean the goals were misguided. Rather, we should take the opportunity to adjust our policy and ensure our collective prosperity. Portland cannot afford another five years of increasingly scarce housing.