Do Record Housing Approvals Show IZ Is Working?

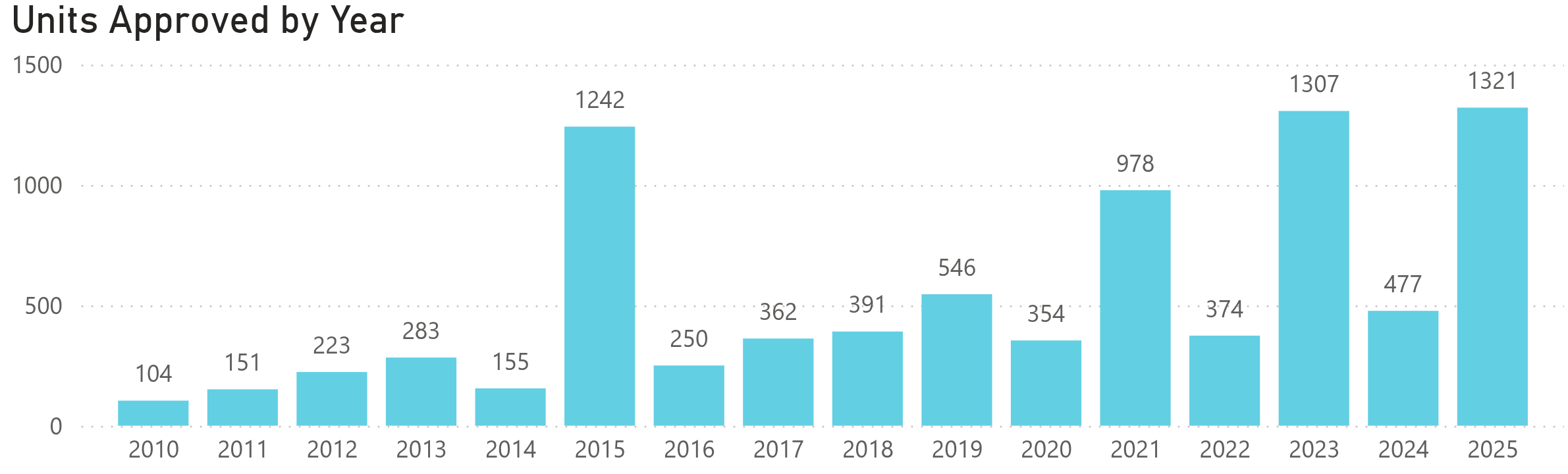

More housing units were approved in 2025 than any year in Portland’s recorded history. A fancy new Housing Dashboard displays these approvals in a collage of charts and data visualizations. This number has been cited as evidence that Portland’s 2020 Inclusionary Zoning ordinance is not so onerous that it stifles development. Yet the Urbanist Coalition of Portland argues that Portland’s Inclusionary Zoning policy is shutting down new housing projects and making housing less affordable. How do we reconcile these two seemingly conflicting assertions? We present our reasoning here.

In 2015, Portland passed its initial IZ ordinance, requiring 10% of units in projects of 10 or more units to be affordable to households making 100% of Area Median Income (AMI). In 2020, Portland expanded this policy, increasing the percent of affordable units from 10% to 25%, and lowering the affordability threshold from 100% AMI to 80% AMI. In both cases, a developer may choose not to build the required affordable units and instead pay a fee-in-lieu for each unbuilt unit into the Jill C. Duson Housing Trust Fund, which funds affordable housing projects. While we will refer to the first policy as the “initial” or “10%” IZ policy, and the latter as the “expanded” or “25%” IZ policy, we want to be clear that we consider both the percent of affordable units and the required affordability level to be significant to the policies’ outcomes.

Since Portland’s IZ policy was expanded in 2020, it has caused only 12 units of affordable housing to be built without subsidy, and no contributions to the Jill C. Duson Housing Trust Fund. This is concerning, but it doesn’t automatically mean there is a problem. Five years is not a long time when it comes to housing. Going from an idea to a finished building can easily take five years; some phased development plans take over a decade. It can be helpful to look ahead when evaluating a housing policy, and measuring the number of housing units approved by the Planning Department is a common way to do so. An approval means the city has given permission for the project to be built. Approvals let us see trends faster, but they are less accurate.

Approval is a prerequisite to construction, but a unit approved is not a unit built. Developers cancel planned projects all the time, particularly when financial or regulatory environments are volatile or uncertain. A developer does not incur substantial regulatory fees until applying for building permits, so a project may change substantially even after its initial approval. Furthermore, a unit approved after 2020 does not necessarily mean it has been subject to 2020’s expanded IZ requirement. Affordable housing projects, for instance, are not subject to IZ, and their size and advancement relies on the availability of financing from HUD and other public sources. Projects are subject to the IZ rules at the time they applied, or at the time they submitted a Master Development Plan (MDP), which can lock in inclusionary zoning rules for years.

If you look at the approvals graph on Portland’s housing dashboard, they appear healthy:

But looking at approvals alone can be deceiving. The expanded 25% IZ policy has not applied to the vast majority of approvals. We went project by project to understand the details of those approvals. (Mouse over to view individual project details.)

Note: our graph has an additional 73 units approved in 2025 because at time of writing Old Port Square Tower is not yet in the City Housing Dashboard.

Our graph is a little more complicated, but it creates categories that can tell the story of our housing construction:

Cancelled: These units will never be built.

On hold: These projects are not currently going forward and will not proceed unless conditions change.

Changed to hotel: These units will not be built and a hotel is being built in their place.

Subsidized/Public: These projects have received a subsidy or are public housing projects. The subsidy can include: Historic Tax Credits, MaineHousing, Low Income Housing Tax Credits, an Affordable Housing TIF, or money from the Jill Duson Housing Trust Fund. These projects have received funding that almost always has stricter affordability levels than IZ requires and the funds allow projects to make sense financially.

<10 Units: Single-family homes and other buildings with little housing are exempt from inclusionary zoning.

No IZ: These projects received approval (or their MDP received approval) before Inclusionary Zoning was in place.

10% IZ: These projects received approval (or their MDP received approval) while the IZ policy required 10% of units affordable and restricted to those making 100% of the Area Median Income

25% IZ: These projects were approved under the newest IZ rules: 25% of units affordable and restricted to those making 80% of the Area Median Income

Looking at the breakdown of projects, approvals look much less healthy. A substantial portion of the growth in approvals is downstream of increased housing subsidy, particularly after 2020. This growth in subsidized development is great! We have a housing crisis, we should be investing public money in building housing. It is concerning, however, that approvals for unsubsidized housing units have not grown at the same rate. Worse, some of these subsidized projects are developers of market-rate housing securing funding so they can meet IZ requirements by building a fully-affordable housing project in a building adjacent to their market-rate housing. It may appear as though IZ is leading to the construction of affordable units, but this subsidy is already earmarked for affordable housing, and will be spent to build affordable housing with or without inclusionary zoning. The problem becomes a crisis when even market-rate development requires subsidy as a default. When all projects require subsidy, the pace of development cannot scale with the pace of housing demand, and instead can only scale with the availability of public subsidy. The fact that this level of subsidy may not continue in the same way, at least in the near future, should cause even greater alarm.

What about any unsubsidized projects? In 2025 – the year with the most approvals – the number of approved units that were subject to the expanded 25% IZ policy and did not plan to apply for subsidy was worryingly small . The single approved project that was exempt from IZ under an MDP contains nearly as many units as all of the 25% IZ projects combined. The other years were even worse, with the overwhelming majority of projects being the result of subsidy, or having applied under or locked in 10% IZ.

To remove the noise of cancelled, small, or subsidized projects, we created a graph of only projects where IZ applies (or would have applied prior to 2015):

On this graph, you can more clearly see that both the initial enactment of and subsequent expansion of Inclusionary Zoning policies were both followed by an immediate and substantial drop off in units entering the housing production pipeline. Production was trending upwards between 2010 and 2015; it fell abruptly in 2016 with the enactment of the initial 10% IZ, followed by another upward trend of 10% IZ projects through 2021. After IZ was expanded to 25% in 2020, very few projects were approved until 2025. Notably, 2025 also happens to be the first year that projects enabled by ReCode were approved. ReCode did a lot of things, but one major change was allowing for more housing in more places. After it was passed, we can observe an increase in approvals.

So does this mean Portland’s expanded IZ policy is now sustainable thanks to ReCode?

Portland passed its current expanded IZ policy five years ago, which is not a lot of time to analyze policy outcomes. ReCode was passed a little over a year ago, so evaluating its effect is even harder. We can look earlier in the project pipeline by considering application date rather than approval date. However, the status of projects that have not been approved are even more uncertain. Below is a graph grouped by application year instead of approval year. There is currently one submitted application for a project awaiting approval: 410 Auburn.

On this graph, we can see the effect of IZ policy a bit more clearly. The inclusionary zoning is locked in in at the time a project applies, so for the most part the IZ category tracks the policy that was in place at the time, with two notable exceptions: Thompson’s Point (locked in no IZ while the expanded policy was in place) and Foreside (locked in the initial IZ while the expanded policy was in place). These projects have Master Development Plans, which allow them to lock in zoning for several projects and then apply later for each individual project. The ReCode line here shifts back a year because there were several projects made possible due to ReCode that applied in 2024. These projects would not be approved until 2025, so the approvals spike appears in 2025 while the applications spike is in 2024.

What is particularly concerning about this graph compared to the approvals graph is how few projects applied in 2025. If ReCode had made the expanded IZ policy sustainable, we would expect to see many applications after it was enacted. This is not the case. Only one project subject to the expanded IZ policy applied in 2025, and there is a significant chance that that project will be scaled down or cancelled. This graph is consistent with ReCode enabling a few particular projects proposed before ReCode was passed , but does not demonstrate a sustained shift in housing production. For example, heights were broadly increased downtown. So far, only Old Port Square Tower has taken advantage of this, perhaps because the developer has been planning a tall building for this site since at least 2016, per an article in the Press Herald.

Project Details

We have been looking at graphs and aggregate data so far, but in Portland we don’t have a lot of projects. In fact, there have been so few projects proposed under the new 25% IZ without subsidy that we can list them all:

Winchester Woods: This is a Planned Residential Unit Development (PRUD).This was a tool before LD2003 and ReCode to allow for multi-family housing in predominantly single-family neighborhoods. As a PRUD, the project was able to get 25% additional units.

Status: Complete

Units: 48

IZ Compliance: Built 12 80% AMI Units

985 Forest Avenue: All of the units in this project already existed; they were just not legal. This project renovates the existing units to make safety improvements and legalize the units.

Status: Approved, Not started

Units: 18

IZ Compliance: Renovating 5 80% AMI Units

482 Congress: This is an existing office building. The owner started by building two “live-work” units designed for remote workers. They were approved to build two more of these units for a total of four. They have since applied to build 35 units within the building.

Status: Approved, Started construction

Units: 35

IZ Compliance: Planning to Build 9 80% AMI Units

246 Eastern Promenade: This is a luxury condo development on the Eastern Promenade. It replaces an older 16-unit apartment building.

Status: Approved, Started construction

Units: 13

IZ Compliance: Planning to pay into the Jill Duson Housing Trust Fund

Belfort Landing: This project is two 3-story, 25-unit apartment buildings in a predominantly single-family home neighborhood. The site for this project was up-zoned for more housing during ReCode.

Status: Approved, Not Started

Units: 50

IZ Compliance: Planning to Build 12 80% AMI Units

Stroudwater Commons: This project is using LD2003 bonuses to build multi-family development in a predominantly single-family home neighborhood. The developer purchased a multi-acre vacant parcel and is building 13 4-story apartment buildings. It qualified as a Conservation Residential Development (CRD) which was critical to allow them to divide the lot in such a way to fit every building.

Status: Approved, Not Started

Units: 156

IZ Compliance: Planning to Build 39 80% AMI Units (also 39 100% AMI Units to qualify for LD2003)

Old Port Square Tower: This is a luxury condo, hotel, and retail hybrid project. The developer has owned the land for many years so land costs are relatively low. This project was enabled by a substantial height increase in ReCode.

Status: Approved, Not Started

Units: 73

IZ Compliance: Planning to pay into the Jill Duson Housing Trust Fund

411 Auburn: This project is similar to Stroudwater Commons and is being built by the same developer: GreenMars. This project is using LD2003 bonuses to build multi-family housing in a predominantly single-family neighborhood. However, to receive approval they must qualify as a CRD. This project impacts a portion of wetlands that is small enough to be legal but this impact led the planning board to express hesitance to qualify the project as a CRD. It is very possible that this project is scaled down or cancelled.

Status: Not Yet Approved

Units: 130

IZ Compliance: Planning to Build 33 80% AMI Units (also 32 100% AMI Units to qualify for LD2003)

Of all of the projects proposed under the expanded IZ policy, so far only three have begun construction, with just one of those two completing construction. Any of the other projects can still be cancelled. Also, some clear patterns emerge: all of the projects that are proposed are either:

in existing buildings (985 Forest and 482 Congress),

very high-end developments (246 Eastern Prom and Old Port Square Tower), or

multi-family housing in predominantly single-family neighborhoods, usually with a density bonus (Winchester Woods, Belfort Landing, Stroudwater Commons, 410 Auburn).

As the Urbanist Coalition of Portland, we have long advocated for allowing more housing in traditionally single-family neighborhoods, and it is encouraging to see it working. However, the potential for more projects like this is limited. Our LD2003 amendments enabled a lot of housing – in fact, if Stroudwater Commons and 410 Auburn are completed as planned, our amendments would be responsible for allowing more than half of the unsubsidized units under Portland’s expanded IZ policy. But we should not inflate the scope of these changes. These projects are being built on large vacant lots that were originally zoned for single-family homes. The LD2003 changes allow for more marginal density on smaller lots, but we can only get housing numbers like this on large vacant lots, and precious few of these remain in a city like Portland.

Belfort Landing was the result of the priority corridor and node-based upzoning from ReCode. While this node model is consistent with the Comprehensive Plan, the City has focused on adding more residential density in areas immediately surrounding these nodes and corridors rather than in predominantly single-family neighborhoods. The node with the Belfort Landing site is very small and the majority of the neighborhood does not allow for similar projects. During the ReCode process, UCP asked for more upzoning of residential neighborhoods, but that was largely absent from the final ReCode changes. This leaves us with a few sites that make sense, but once they are gone, they’re gone.

UCP is trying hard to make housing work. We have fought for the majority of units proposed under the expanded IZ policy. We have shown up in support at every meeting for Bellfort Landing, despite organized and passionate opposition. Now the city is being sued for approving it, and while this probably won’t kill the project, it could. We have shown up in support of Old Port Square Tower, despite the controversy over such a tall building. We worked to pass the law that allowed Stroudwater Commons and 410 Auburn Street to be built in the first place, representing more than half of the units that are subject to the new IZ policy that are not currently cancelled or on hold. The project at 410 Auburn Street is not yet approved, and the Planning Board has expressed hesitance. We showed up to that meeting to speak in support, and we plan to continue to do so . Even the projects that do pencil under the expanded 25% IZ are controversial. We fight hard for them because with so few projects in our housing pipeline, each one is precious.

We are trying to make housing projects work and this policy makes it a lot harder. Let’s change it.